| Baby Crimson | ||||||||||||||||

| By Bill Radford The Gazette | ||||||||||||||||

| Publication:The Colorado Springs Gazette; Date:Jan 16, 2005; Section:Section A; Page Number:1 | ||||||||||||||||

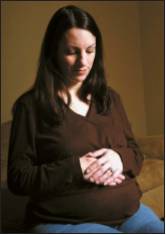

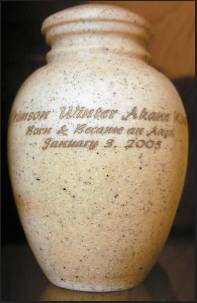

The Kings cherish their time with baby Crimson, although they had just 60 minutes Publication:The Colorado Springs Gazette; Date:Jan 16, 2005; Section:Section A; Page Number:1 Most people’s lives are measured in years. Crimson King’s life was measured in minutes. She was born Jan. 3 at 5:22 p.m. She was pronounced dead at 6:22 p.m. Sixty minutes. Time enough to cry out eight times. Time enough to open her eyes and gaze at her mother’s face. Time enough to create memories for her family that will never fade. “She was beautiful,” her father, Jason King, said days later at the funeral. “From the outside, you would never know anything was wrong with her.” But Jason and Aubrey King knew Crimson never had a chance. The Colorado Springs couple learned 16 weeks into the pregnancy that Crimson had Potter’s syndrome, a rare condition marked by a lack of kidneys. A baby’s kidneys are essential to production of amniotic fluid in the womb. Without the fluid to expand the womb, the baby’s lungs can’t develop properly. Many Potter’s babies are stillborn. Those who survive last for hours at best; respiratory failure is usually the cause of death. For the Kings, those 60 minutes were a gift, particularly the first 10 when Crimson was awake and active. Jason King had heard that Potter’s babies often shudder just before they die. He dreaded it, but that moment, that jolt to Crimson’s tiny 4-pound body, never came. “She fell asleep and just drifted off and her heart stopped. It was very peaceful.” Crimson was not the first loss for Aubrey King, a stay-at-home mom, and Jason King, an active member of the U.S. Air Force Reserve at Schriever Air Force Base. Aubrey King had given birth three times before. Three perfect, textbook pregnancies — Burgundy, now 7, Courtland, 4, and Ashton, 1½. In March, she suffered a miscarriage, but she soon was pregnant again. The Kings, both 33, were hoping for a girl, a baby sister for Burgundy. They were delighted when they learned Aubrey carried twins. They wouldn’t find out for sure until much later, but they always felt the twins were girls. A six-week ultrasound showed no problems. “They looked perfect at that point,” Aubrey King said. In June, at eight weeks, one twin died. That twin, it was discovered, was acardiac, meaning its blood flow was provided by the other twin. It would have had no chance to survive long term. The twins also were monoamniotic, a condition in which identical twins share a common amniotic sac. That condition is accompanied by an increased risk of birth defects and death. Still, there was hope for the surviving twin. In the 15th week, though, Aubrey King knew something else was wrong. Her belly had shrunk. She had lost 2 pounds. An examination revealed she had no amniotic fluid. There was the possibility her sac had ruptured, that amniotic fluid could return. But Potter’s, a condition affecting about 1 in 4,000 births, was another possibility — one confirmed days later. Doctors were clear. The Kings’ baby could not survive outside the womb. The Kings had dreamed of two little babies to cuddle and love. Now there would be none. It’s incredibly tough to shatter a couple’s hopes and dreams and tell them their baby will not live, said Dr. Kevin Weary, Aubrey King’s obstetrician. Crimson Winter Akane King lived only an hour outside the womb, but she lived for more than eight months inside her mother, Aubrey King pointed out. “I wanted her to feel happiness, to be a part of our life, even though she was in the womb, and she was.” When her husband sang in the car, Aubrey King felt Crimson turn toward him. Anytime Ashton let out a scream, Crimson kicked — and kicked hard. Shower time was mother-daughter time. Alone in the bathroom, away from distractions, Aubrey King talked to the life inside her and tried not to let the tears overwhelm her. She was honest with friends and strangers who asked about her pregnancy, telling them she was preparing not for an addition to the family, but for a funeral. Some people refused to believe that nothing could be done in this age of cutting-edge technology and mira- cle babies. Some would tell Aubrey King, “Well, at least you have three children.” As if those three lives meant it was OK to lose a fourth. At other times, Aubrey King was touched by the kindness of others. Strangers often had tears in their eyes upon hearing her story. Weary and the Kings decided to induce labor Jan. 3, at 36½ weeks of gestation. Throughout the difficult months, Aubrey King found a sympathetic ear through an online Potter’s syndrome support group, and in a Jan. 1 posting, she wrote: “Hi all, it’s Aubrey and Crimson. It’s almost time. Right now she is happy, I think, and playing in my tummy. Kicking her legs around. I have been having contractions (ouch) more, and Monday we go in for induction. I want her to be born alive so much. I want to tell her I love her and I want pics of her alive. I am crying more and more these days.” She spent the day before Crimson’s birth close to panic. “I was just so scared about everything,” she said. “Mostly the unknown: Was she going to make it out alive, how was the pain going to be, and how was the hospital going to be, and was everything we hoped for going to happen?” The Kings went to Penrose Community Hospital early that Monday morning. Doctors began to induce labor about 8:30 a.m., using a drug to stimulate contractions. There was a frightening period during which Crimson’s heart rate dropped with each contraction. “We didn’t think she was going to make it out alive,” Aubrey King said. Crimson had some features characteristic of a Potter’s baby: club feet, a short neck, low-set ears. Potter’s babies, because they’re tightly packed in the womb without amniotic fluid, also often have squashedin facial features. But not Crimson. “She was gorgeous,” Aubrey King said. Crimson was placed on her mother’s chest. The umbilical cord, Crimson’s lifeline, was not cut until 10 minutes later, when the placenta detached from Aubrey King’s uterus. It was then that the baby’s life began to slip away. “I knew I had to be strong,” Aubrey King said. “I had all this stuff I wanted to say to her, and I didn’t want to be crying through it.” Shortly after Crimson was delivered, Weary found the inch-long form of her twin sister, Violet. “It was a miracle they were able to find her tiny, little body,” Aubrey King said. For most of the 60 minutes, Aubrey King held Crimson. Jason King held her, too, but mostly he took pictures. It helped, he said, to stay busy. At 6:22, a nurse declared Crimson dead. “I lost it,” he said. The day after, still in the hospital, Aubrey King cried until her eyes swelled shut. She kept Crimson’s body with her until she left the hospital midday the next day, Wednesday. It was not grotesque, she said. It was just like holding a sleeping baby. “Leaving the hospital and leaving her body was the hardest thing I’ve ever had to do in my life.” The funeral was Jan. 8, a wind-ravaged Saturday, at Evergreen Funeral Home. Crimson lay in a basket, looking like a porcelain doll with its eyes shut. Violet was there, too. The family wrote messages on a poster for all to read. Aubrey King wrote, “Crimson, my Crimmy, I love you more than you will ever know. My arms ache without you in them.” Jason King told mourners of the difficult pregnancy, of the tiny corner of his mind that had held out hope for a miracle, of the beautiful baby he’ll never forget. Aubrey King told of the grand life Crimson had inside her and of those final minutes in her arms. Four-year-old Courtland, fidgeting and running around during most of the service, raised his hand to speak near the end. “Goodbye, Crimson, and goodbye, Violet,” he spoke into the microphone. “I love you.” The Kings decided to have Crimson and Violet cremated. Tuesday, they took home the urn containing the twins’ ashes. They put it on a shelf in their bedroom, part of a shrine that includes photos, a lock of Crimson’s hair, and blankets and clothing from the hospital. There’s also a sculpture of a couple holding a baby — a Christmas present, Aubrey King said, from her husband and Crimson. It’s hard to leave the bedroom, she said. To leave Crimson. But life goes on. Her children need her. Her husband needs her. Tuesday night, she found Courtland — “Mr. Testosterone,” she calls him — sleeping with a doll. What was he doing, she asked. Who was that? Violet, he answered. “I said, ‘Is that the big one or the little one?’” “The little one,” Courtland answered. Aubrey King longs to hold Crimson again. She pictures what it would be like if Crimson had survived, if both twins had lived. She’s grateful Crimson was a part of their lives, even so briefly. “I treasure every single minute I had with her.”

Contact the writer: Support Networks: To Our Readers: There are stories of medical wonders, of babies who survive despite the odds. But not all babies survive. When Aubrey King complained to her mother, Karleene Thompson, that no one writes about those situations, Thompson contacted The Gazette. The Kings welcomed a Gazette reporter and photographer into their lives in the weeks before and after the birth — and death — of Crimson King to tell the story of how such a short life can have a lasting impact. | ||||||||||||||||